By Edward Hall

For a long time, comparing wild apes to humans was a line that many scientists were unwilling to cross. Even now, the idea that humans and wild apes are similar is controversial in some circles. While anthropomorphising our bonobo cousins presents some challenges (as we should be careful to view them always as wild animals), I believe it may be helpful in understanding them as complex emotional creatures and us as products of a wild past.

Motherhood is an important part of bonobo society; through it, we are shown a side of the wild that is undeniably familiar.

Bonobo Mothers and Sons

You may have heard that a boy’s first true love is his mother. Beyond nursing for nutrition, the mother’s presence in a child’s early life is essential to their development. I believe the quintessential human ‘mother’ is the individual who first models the virtue of kindness to the infant. In bonobo society, the mother’s influence on sons is crystal clear. Males with surviving mothers show a much higher mating success compared to higher ranking males without surviving mothers.

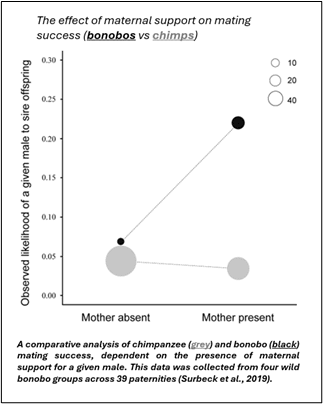

Surbeck and colleagues (2019) compared the mating success of wild bonobos and wild chimpanzees depending on whether a male’s mother was present. This study found that bonobos with a mother present were approximately four times more likely to sire offspring than those without present mothers.

For chimpanzees, there seems to be little (or, perhaps, an adverse) effect under the same conditions. This is one way in which the traumatic effects of early separation from maternal support can cause long-lasting harm for bonobos. This is also why orphans at the Lola ya Bonobo sanctuary are paired with human ‘Mamas’ (surrogate mothers), who provide the foundational love and care that all young bonobos need to grow up healthy.

When bonobos become orphaned, they often develop psychological abnormalities as a result of severe stress, such as a reduced likelihood to console others and a reduced ability to demonstrate appropriate prosocial responses to others’ emotions.

We now know that the mother-son relationship is an essential element of bonobo society. Strong mother-son bonds are beneficial to the overall group because bonobos are a male-philopatric species, meaning that the males stay with their natal groups for life, whereas the females migrate upon reaching sexual maturity.

Bonobos and the Grandmother Hypothesis

Of course, everything in nature is about survival, so we’re prompted to ask: “Why has this trait evolved in the species?” The answer to this is relatively simple: the grandmother hypothesis. The grandmother hypothesis is an attempt to explain why women live longer than men in some mammalian species. The concept of any animal living beyond its ability to reproduce is unusual, but not for many great apes. Menopause is natural for humans (and there is evidence of captive chimpanzees and bonobos showing post-reproductive symptoms, too).

The grandmother hypothesis proposes that, although older women are not able to physically reproduce, they can still contribute to the reproductive success of their bloodline. They do this by sharing in caregiving for their grandchildren and socially tutoring them: providing support in mating interactions and conflicts. This hypothesis exposes another dimension of motherhood shared between our species, where the role of caregiver is shared between adults in the community.

It could also be described as a “feminisation of nature” because, the closer we look, the more evident it becomes that nature (especially for the ape) favours the long-term survival of women over men, as women may have the greater influence on species survival. So, being a bonobo with a mother is great, especially if you’re male, but what social benefits does motherhood provide for the mothers themselves?

Like Us, Bonobo Mothers Bond and Mourn

The mother-bonding hypothesis proposes that females are closely bonded by their shared experiences as mothers, and therefore motherhood is essential to the ‘matriarchy’ we observe in bonobo groups. In a study by Cheng and colleagues (2022), infant mortality appeared to weaken the social bond between bonobo mothers, implying that the condition of being an active mother has some positive effect on female bonding.

This study also touched on a factor of bonobo motherhood that is worth discussing: mourning, an expression of sorrow at the loss of a loved one, which is particularly strong when a mother loses her child. In Cheng et al.’s study, a mother called Peche discovered her three-year-old daughter, Prune, dead at the bottom of a tree. The cause of death was unknown, and no obvious injuries were present on the body. Peche carried Prune’s corpse for two days, where she groomed the infant as if it were alive. Two sub-adult females also took an interest, grooming and swatting away flies.

That evening (after two days of mourning), the group ate the corpse. In wild bonobo society, the cannibalism of deceased loved ones is not necessarily unusual and does not imply that the subject was not loved. Rather, the infant (whose body decomposes rapidly in the humid Congo jungle) ceases to remind the mother of her own child and instead presents some nutritional value to the group.

Mourning in great apes is now a well-documented phenomenon, once thought to be unique to human beings. The mother-child bond seen in bonobos largely mirrors that of our own species, from mourning to the mother-bonding hypothesis that many of us have experienced firsthand, either through being a mother or watching your own mother socialise with your friends’ mothers.

Bonobos – Much Like Us

We have long operated under the false assumption that human beings are separate from the rest of the animal kingdom, and that certain behaviours (kindness, empathy, intelligence, and language) are exclusive to our species, the self-professed ‘most remarkable’ of all life. In his 1925 book Almost Human, psychologist Robert Yerkes was perhaps the first Western mind to distinguish a bonobo from a chimpanzee, before the concept of a separate Pan species was even conceived.

Yerkes studied what he thought were two young chimpanzees: a male bonobo called Prince Chim, and a female chimpanzee called Panzee. Yerkes wrote of Chim: “If I were to tell of his altruistic and obviously sympathetic behaviour toward Panzee, I should be suspected of idealizing an ape.”

Motherhood unites us with our wild cousins.

A man who was very much a product of his time, Yerkes was cautious not to anthropomorphise apes, in order not to alienate himself from the scientific zeitgeist. It wasn’t until Jane Goodall’s work with the chimpanzees of Gombe in the 1960s that science even began to re-examine the man-animal distinction. When it comes to bonobos, I think we still have a long way to go to achieve widespread understanding of them as a reflection of ourselves. Motherhood is a quality that unites us with our wild cousins, where the man-animal distinction is unquestionably blurred.

Edward W. Hall is an Australian writer, educator, and bonobo ambassador. His love of bonobos is driven by the belief that their philosophy for survival may help humans to live more peacefully. One day, he hopes to travel to Africa and participate in a long-term study of bonobos in the wild. Follow him on Instagram.

REFERENCES

Cheng, L., Shaw, A., & Surbeck, M. (2022). Mothers stick together: how the death of an infant affects female social relationships in a group of wild bonobos (Pan paniscus). Primates, 63(4), 343–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-022-00986-2

Goodall, J. (1964). Tool-Using and aimed throwing in a community of Free-Living chimpanzees. Nature, 201(4926), 1264–1266. https://doi.org/10.1038/2011264a0

Herndon, J. G., Paredes, J., Wilson, M. E., Bloomsmith, M. A., Chennareddi, L., & Walker, M. L. (2011). Menopause occurs late in life in the captive chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes). AGE, 34(5), 1145–1156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-011-9351-0

Kordon, S., Webb, C. E., Brooker, J. S., De Waal, F. B., & Clay, Z. (2024). Factors shaping socio-emotional trajectories in sanctuary-living bonobos: a longitudinal approach. Royal Society Open Science, 11(12). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.240435

Laméris, D. W., Staes, N., Salas, M., Matthyssen, S., Verspeek, J., & Stevens, J. M. (2020). The influence of sex, rearing history, and personality on abnormal behaviour in zoo-housed bonobos (Pan paniscus). Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 234, 105178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2020.105178

Martin, J. E. (2002). Early life experiences: Activity levels and abnormal behaviours in resocialised chimpanzees. Animal Welfare, 11(4), 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0962728600025148

Stevens, J. M. G., Vervaecke, H., De Vries, H., & Van Elsacker, L. (2006). Social structures in Pan paniscus: testing the female bonding hypothesis. Primates, 47(3), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-005-0177-1

Surbeck, M., Mundry, R., & Hohmann, G. (2010). Mothers matter! Maternal support, dominance status and mating success in male bonobos (Pan paniscus). Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences, 278(1705), 590–598. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.1572

Tokuyama, N., Moore, D. L., Graham, K. E., Lokasola, A., & Furuichi, T. (2017). Cases of maternal cannibalism in wild bonobos (Pan paniscus) from two different field sites, Wamba and Kokolopori, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Primates, 58, 7-12.

Van Leeuwen, E. J., Staes, N., Verspeek, J., Hoppitt, W. J., & Stevens, J. M. (2020). Social culture in bonobos. Current Biology, 30(6), R261–R262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.02.038

Yerkes, R. (1925). Almost Human. The Century Co., New York & London.